Great Historic Investments: Ben Graham and The Northern Pipe Line Corporation

An obscure company selling below net cash (and liquidation value) with consistent earnings and an 8% dividend yield.

I have learned much by looking at the great investments of the past. I think it’s an invaluable exercise. This is my first case study in that vein. With these case studies I hope to break down an investment as simply as possible, but no more so. I hope to write in such a style that anyone could understand the investment thesis, regardless of financial knowledge.

Benjamin Graham

Benjamin Graham is the father of Value Investing. His fund, the Graham-Newman Corporation was established in 1936 with an initial investment of $600,000. Over the next 20 years he returned a compound annual growth rate of 20% turning that initial investment into $23,000,000, a 38x return over 20 years. His investment in the Northern Pipeline Corporation is a textbook example of his investing philosophy.

A Discovery

In 1926, Benjamin Graham was reading through reports to the Interstate Commerce Commission. In these reports he found references to public companies that he had never heard of, with the only source being the line: “taken from their annual reports to the Commission.” He soon found himself on his way to the Commission’s library to find those annual reports. In those reports he found an interesting group of pipeline companies.

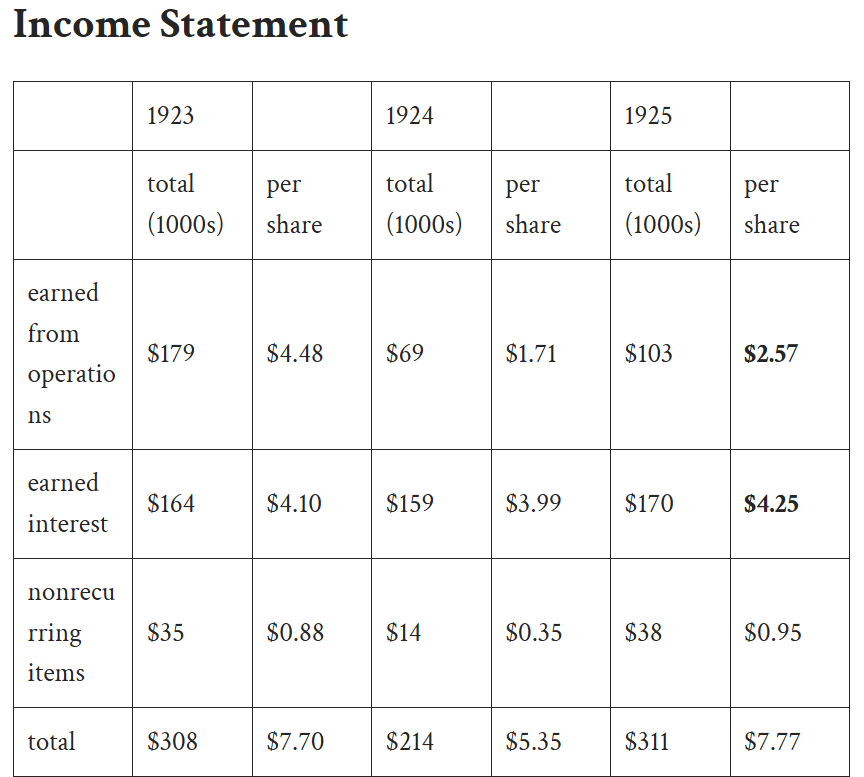

Originally carrying oil to Standard Oil refineries, 8 pipelines were spun off in 1911 as part of an antitrust decision against Standard Oil. Each company was small and published limited financial information – only a one line “income account” and a few lines for a “balance sheet”. All of which I include in this post.

While reviewing each of these spin offs, Graham’s noticed the Northern Pipe Line Corporation. What he found was a quintessential Graham investment – a “Net-Net”, a company selling for less than the cash on its balance sheet.

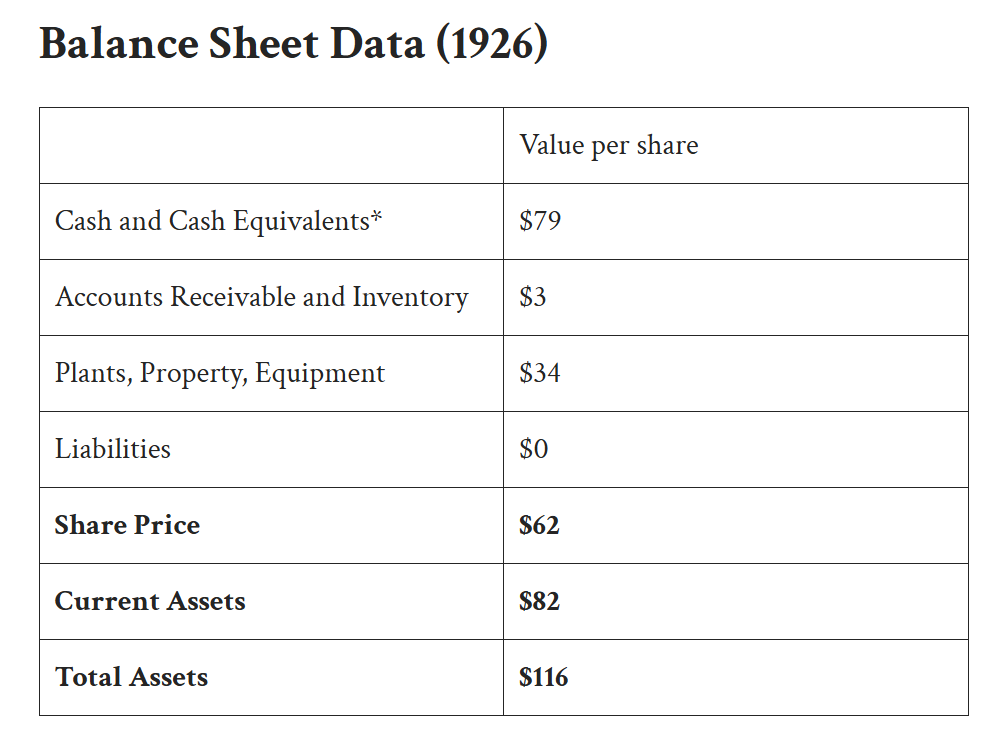

Graham simply took the value of all current, tangible and easily liquifiable assets (most of which were cash) subtracted debts and divided that value by the share count. By doing so he arriving at a tangible book value per share of $82. At a share price of $62, the stock was selling at a 25% discount.

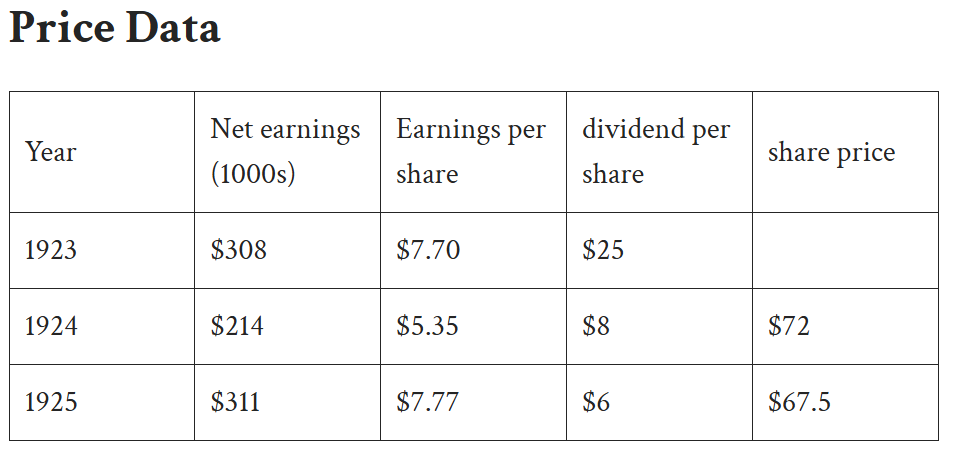

Sometimes this occurs when the company is burning through cash quickly, where an investor might not expect that excess cash value to be there a year from now. With that in mind, Graham looked at the price and earning data:

Note: The stock has 40,000 shares of common stock.

That was not the case here. Earnings were consistently positive and the company had a dividend yield (dividends per share/share price) of 8.8%. Incredibly more than 180% of earnings were returned to shareholders in dividends.

Now Graham considered the nature of these earnings.

$4 per share came from the earned interest on cash and cash equivalents. $2-4 per share came from the operations alone.

Now take a moment in Ben Graham’s shoes. Ask yourself, how much is this business worth?**

When I answer this question, I first price the business conservatively at the value per share of it’s current assets minus its liabilities: $82. I would also value the future cash flows of the business based on it’s operational earnings. In this case $2.57, at a conservative multiple of 5, that gives us $82 + $12.85 = $94.85. Selling at $62, NPL was selling at a ~33% discount.

Unlocking Value with Activism

Ben began buying shares. Over a year, he was able to buy 2,000 shares of Northern Pipe Line’s 40,000 shares, making him the largest shareholder.

Now the challenge lied in unlocking the intrinsic value of a company, so he brought up this price disparity to management. When speaking with Graham the president of Northern Pipeline insisted that returning the excess cash to shareholders was not possible for three reasons: the bonds that made up most of the cash and cash equivalent portfolio were needed to cover the stock’s $100 per share par value; they needed to replace the current pipeline; and finally, they might want to extend the line in the future. In summary, he insisted that “The pipeline business is a complex and specialized business about which you know very little; but in which we have spent a lifetime. We know better than you what is best for the company and the stockholders. If you don’t approve of our policies, you should sell your shares.” [1]

Ben attended the annual meeting in January 1927 with a resolution to sell the bonds and to pay the surplus cash to shareholders. However he had neglected to bring someone to second his motion to present the memorandum, it was not read and the meeting was adjourned.

The next year, Ben had bought more shares of Northern Pipe Line and this time solicited proxies to vote in favor of his position.

At the 1928 annual meeting, Ben came supplied with proxies for 38 percent of the shares, ensuring the election of two directors to the board.

A few weeks after the meeting, the president agreed to liquidate the bonds and distribute $70 per share. The $70 distribution plus the remaining $30 share price of Northern Pipe Line meant that Graham unlocked significant value for shareholders and saw a 53% return on his $64 investment.

Summary

The Northern Pipe Line investment is a textbook illustration of Benjamin Graham’s investment philosophy. Graham was focused on finding safe investments that were mathematically clear and that provided a solid margin between intrinsic value and market value. Graham saw opportunity when: A Company’s Market Value was less than Current Assets−Total Liabilities.

Warren Buffett sometimes refers to these opportunities as cigar butts. “If you buy a stock at a sufficiently low price, there will usually be some hiccup in the fortunes of the business that gives you a chance to unload at a decent profit, even though the long-term performance of the business may be terrible. I call this the “cigar butt” approach to investing. A cigar butt found on the street that has only one puff left in it may not offer much of a smoke, but the “bargain purchase” will make that puff all profit.”

Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway: Letter to Shareholders (1989).

Net-nets like Northern Pipeline are vanishingly rare in the current market (all but one cigar net-net on the NASDAQ today has a huge cash burn rate and massive share dilution), but these opportunities were bountiful in the 1930’s when security prices were depressed.

Graham’s ideas were innovative at the time and they established key ideas about valuation that were picked up by later value investors.

A few things we can take away from this investment:

A conservative and intelligent investor should look for opportunities where a company’s market value is less than its net current asset value. This provides some margin of safety regardless of future cash flows (which we can not know for sure).

These opportunities exist because the market prices things separately from their intrinsic value.

In order for value to be unlocked quickly, a catalyst helps. In this case that was an activist investor motivating management to return cash to shareholders. ***

This is the core of value investing. Buy an asset for less than its intrinsic value, the difference between the two is your margin of safety and expected profit.

Footnotes:

*Northern Pipe Line’s cash assets were mostly in high quality railroad bonds.

**You may also ask: What caused the discount? How could one catalyze the value of this business to reach its fair price? How much of my portfolio should I dedicate to this?

*** Buffett refers to these opportunities as control situations, where you can either control or influence the company to unlock value. I could repeat this same exercise for Buffett’s investment in Dempster Mill, but that just introduces the idea of how to value inventories, accounts receivable at a discount as compared to cash (at 100% of its value).