The Risks of the US For-Profit College Industry: Illustrated With A Post-Mortem of Corinthian College

At first glance, American for-profit colleges would seem to be an attractive investment. You sell an intangible “hope” that is always in demand. You are a service company so your gross margins are good (typically 50%) and your operating profits are good (typically 10%). You can place your colleges anywhere, and most of your costs are variable, so you can scale accordingly.

Today, for-profit colleges operate in the context of worker shortages, a weak labor market, and a chronically underfunded public education system. Furthermore, enrollment and profits boom during economic downturns and technological dislocations, making them a good counter cyclical play (stay tuned).

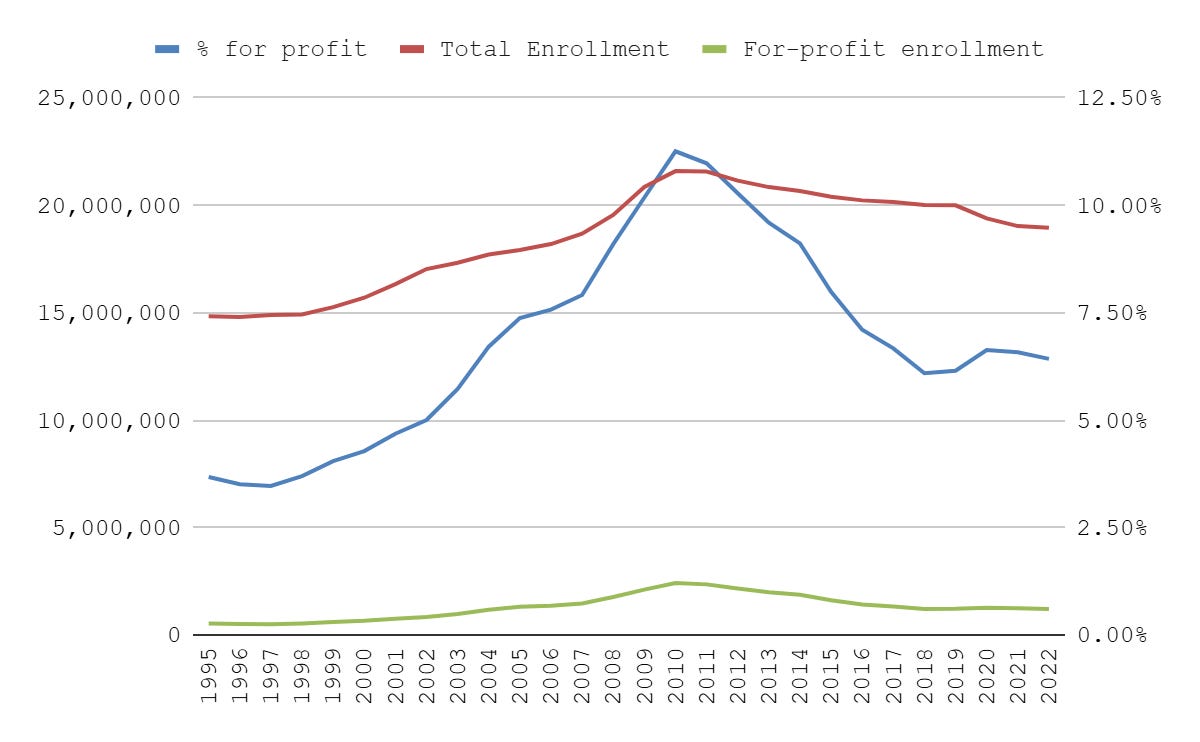

For-profit enrollment booms during recessions.

Source: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_303.20.asp

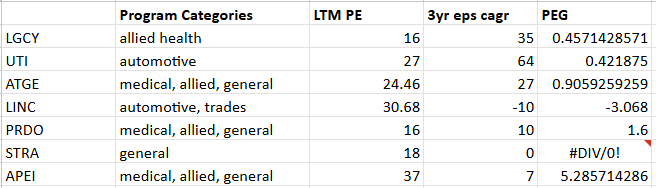

That’s why I looked through all the publicly traded for profit colleges (operating or not). This list included: PRDO, UTI, STRA, APEI, ESIN.Q, NAUH, ATGE, LINC, LGCY.

In my research I found that these investments have a history of blowing up suddenly and spectacularly. To list a few you may have heard of: ITT Technical Institute (ESIN.Q) , National American University (NAUH) and Corinthian Colleges (COCO).

In this write-up I will talk about the dynamics of this industry, and then review the corporate history of COCO specifically, which should highlight the major risks in this industry that anyone considering investing in the space should appreciate.

Background of the for-profit college industry

In theory, the idea behind for-profit education is simple. If there are skill gaps in the economy, for-profit colleges can attract capital to build education programs to fill that gap. Competition should make sure that the best survive. However, in practice, it is not quite that simple.

For profit colleges are easy to set up. You develop a curriculum, lease a space, hire teachers and advertise your product. You may want to become an accredited program to increase the odds of graduate placement and increase student entry rates, but colleges can and have started without accreditation (Trump University for one). You also compete with established non-profit or public schools that have established programs, better reputations, larger employer networks, no profit requirement, and lower student acquisition costs. Community and public programs are of course subsidized. In-person programs compete with online offerings nationally. This is to say that non-profits have serious competitive advantages over for-profits, which is demonstrated by their lower tuition cost/post grad salary ratios (and associated lower default rates).

Profits in the industry structurally tend to be fleeting, as either non-profit schools expand offerings (attracting the higher performing students, leaving lower performing students in for-profit schools, which in turn decreases post grad outcomes and payment), or other for-profit operators quickly scale up their offerings, capping your growth. For this reason you can think of for-profit schools as marginal producers, high on the cost curve.

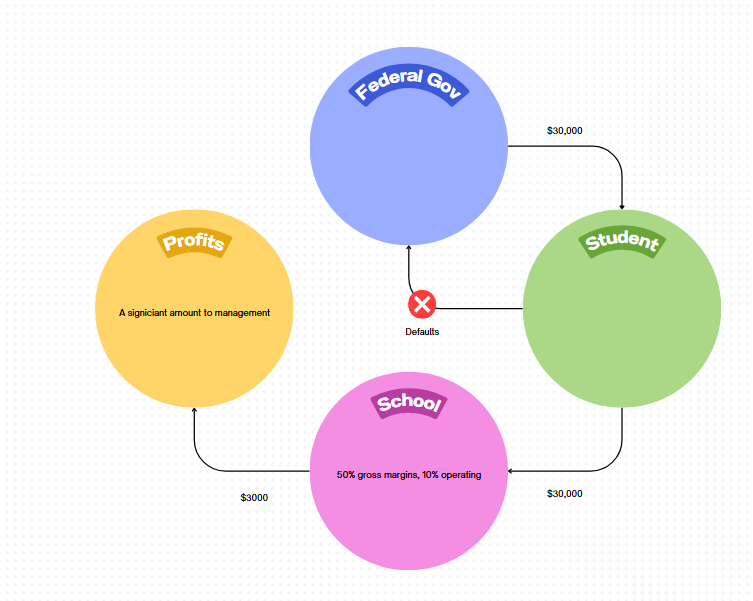

Some for-profit colleges work with employers to offer tuition reimbursement, and may offer promotions, discounting on these programs, but there are few discounts/scholarships beyond that. Most funding (~90%) comes from the federal government, mostly from Title IV funds. This number was at one point close to 100%, but during the Obama administration, regulations were passed that capped total Title IV federal funding at 90% of total tuition. Naturally for-profit schools try to get as close to that number as possible.

In such an environment a moral hazard develops:

If the person using the service isn’t the one to pay for it, and you as the supplier are incentivized to make tuition and enrollment as high as possible, you tend to get perverse incentives. Add in that many loan programs include living stipends (GI BILL) and you get targeting of the communities with access to those programs - which will often include false advertising.

These loans post a significant cost to taxpayers (typically a bi-partisan issue), and so from time to time the federal government cracks down on the industry.

“Every decade or two since WWII, lawmakers have loosened oversight of federal aid to career colleges run by for-profit companies only to be disappointed by rampant abuses. The scandals prompt regulators to clamp down, only to later be convinced by industry executives that the schools have cleaned up their act.”(The Century Foundation)

A few major regulations have developed over time.

Key regulations in the for-profit education industry

The 90/10 Rule

Description: This rule is a market viability test. It mandates that a for-profit college must get at least 10% of its total revenue from sources other than federal student aid (Title IV funds). The goal is to ensure that the education is valuable enough for someone—a student, a state, or an employer—to pay for it without federal subsidy.

Key Metrics: Look for the 90/10 ratio itself, which is a required disclosure. A ratio approaching 90% is a major risk factor, as violating the rule for two consecutive years results in the loss of all federal funding.

Legal Status: No changes yet.

Gainful Employment (GE)

Description: This Obama-era regulation aimed to protect students from low-performing career education programs that result in high debt burdens. It measured whether graduates earned enough money to reasonably pay back their student loans. Programs that consistently failed the debt-to-earnings test would lose access to federal student aid.

Analyst Metrics: When active, analysts focus on a company’s percentage of programs that are failing or at risk of failing the debt-to-earnings metrics. This represents a direct threat to future revenue streams.

Legal Status: This rule is a political football. The first Trump administration rescinded it. The Biden administration reinstated it. A Trump 2.0 administration would almost certainly begin the process to rescind and replace it again with a more institution-friendly transparency rule. This has not been done yet.

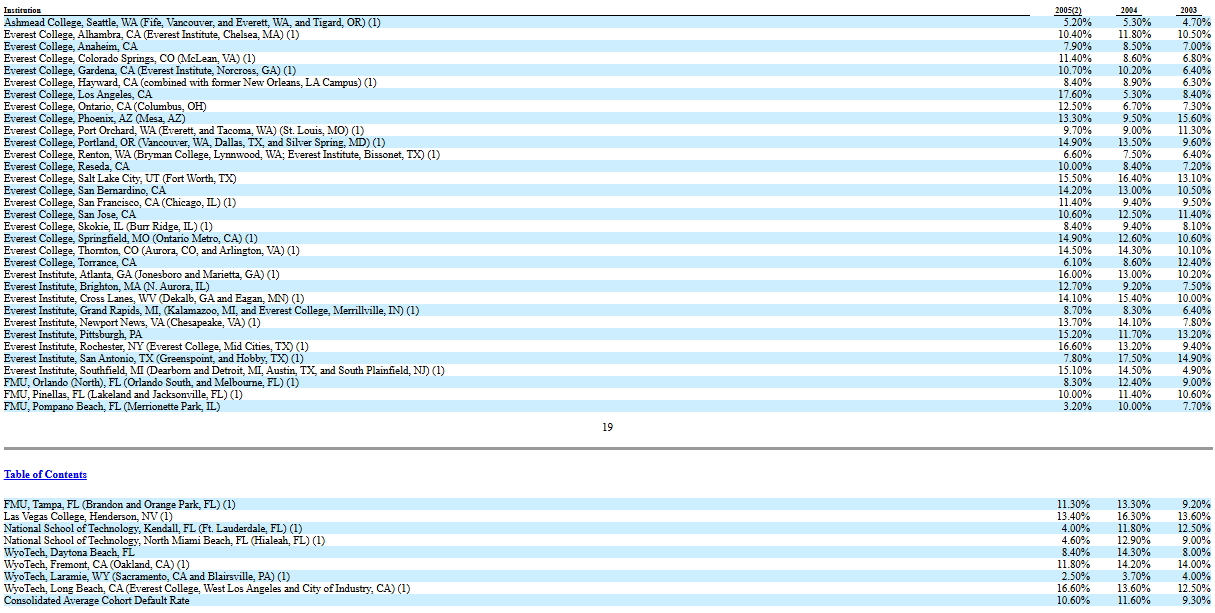

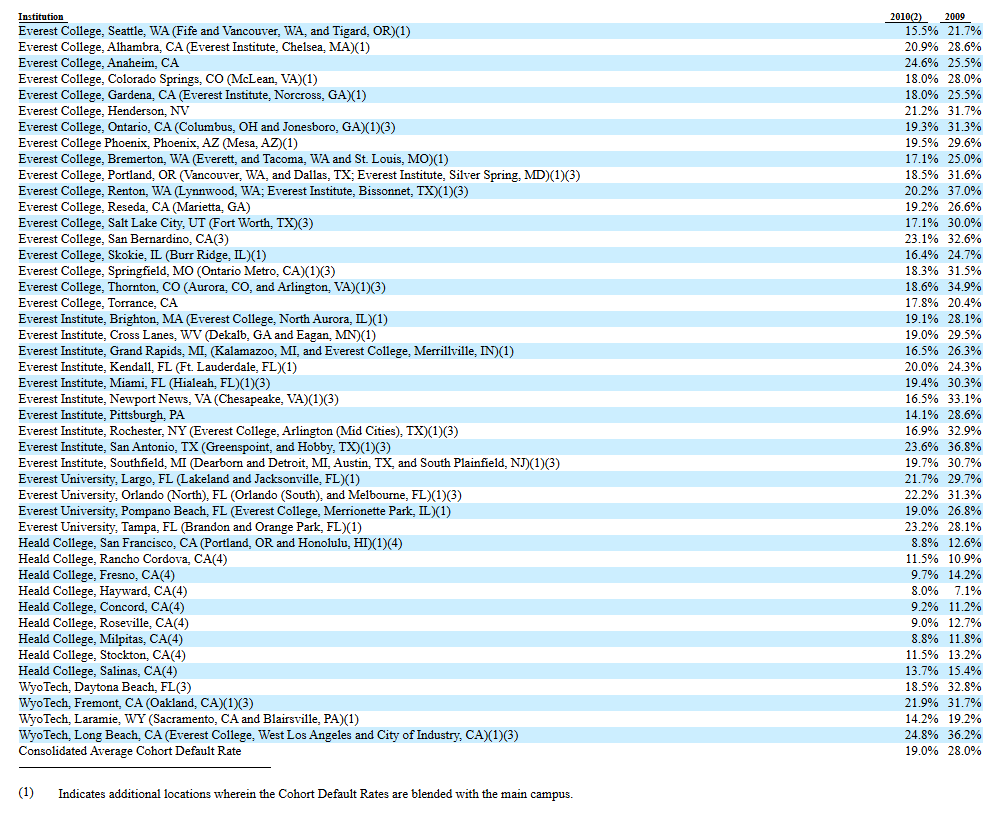

Cohort Default Rates (CDR)

Description: This is one of the oldest accountability measures. The Department of Education tracks the percentage of a school’s former students who default on their federal student loans within three years of entering repayment.

Analyst Metrics: The official 3-year Cohort Default Rate. If a school’s CDR exceeds 30% for three consecutive years or is above 40% in a single year, it risks losing eligibility for federal aid. Analysts watch for any upward trend in this rate.

Legal Status: This is active, It is broadly supported and would remain in effect and unchanged.

Borrower Defense to Repayment (BDR)

Description: This rule allows students to have their federal loans forgiven if their college misled them or engaged in other misconduct (like making false promises about job placement). The Department of Education can then hold the institution financially liable for the discharged loan amounts.

Key Metrics: The dollar value of pending BDR claims against the institution and any related liabilities recorded on the balance sheet. Also look for required letters of credit the school must post as collateral.

Legal Status Under Trump 2.0: The first Trump administration replaced the Obama-era rule with a much stricter version that made it harder for students to receive forgiveness. No change in the second term yet.

Incentive Compensation Ban

Description: This rule prohibits schools from paying commissions, bonuses, or other incentive payments to their admissions and recruitment staff based on their success in securing student enrollments. Its purpose is to prevent predatory, high-pressure recruiting tactics.

Key Metrics: Monitor lawsuits, whistleblower claims, and government investigations related to recruiting practices. High marketing and admissions expenses as a percentage of revenue can also be a red flag for aggressive tactics.

Legal Status: This is a core part of the Higher Education Act. It is active, but enforced by the department of education, which may no longer exist.

Financial Responsibility Standards

Description: The Department of Education uses a set of financial ratios to calculate a single “Composite Score” from 0 to 3, which measures the school’s overall financial health.

Key Metrics: The Composite Score is the single most important metric here. A score below 1.5 triggers heightened cash monitoring and oversight. A score below 1.0 means the school is not considered financially responsible and may need to post a significant letter of credit to continue receiving federal aid.

Legal Status: It is active, but enforced by the department of education, which may no longer exist.

Program Participation Agreements (PPA)

Description: A PPA is the master contract between a school and the Department of Education. To receive any federal student aid, a school must sign a PPA, agreeing to comply with all applicable laws and regulations. The Department can place a school on a provisional PPA, indicating heightened scrutiny.

Analyst Metrics: The status of the PPA (fully certified or provisional). A provisional PPA is a major red flag, as it can restrict growth and signals the Department has serious concerns.

Legal Status: Active, no changes to law yet.

Accreditation

Description: Accreditation is a non-governmental, peer-review quality assurance process. An institution must be accredited by a recognized agency to be eligible for federal student aid. It is the foundational “license to operate.”

Key Metrics: The accreditation status of the institution and its programs. Look for any “warning” or “show-cause” status from an accreditor, as this can signal serious operational or quality issues that could threaten the school’s existence.

Legal Status: The requirement for accreditation would remain. However, the first Trump administration created a more permissive environment for accrediting agencies themselves. This trend will likely continue.

In summary, the main forces that for-profit colleges face are the business cycle (high employment is bad for business), free competition, and periodic government crackdowns.

A Post-Mortem of Corinthian College

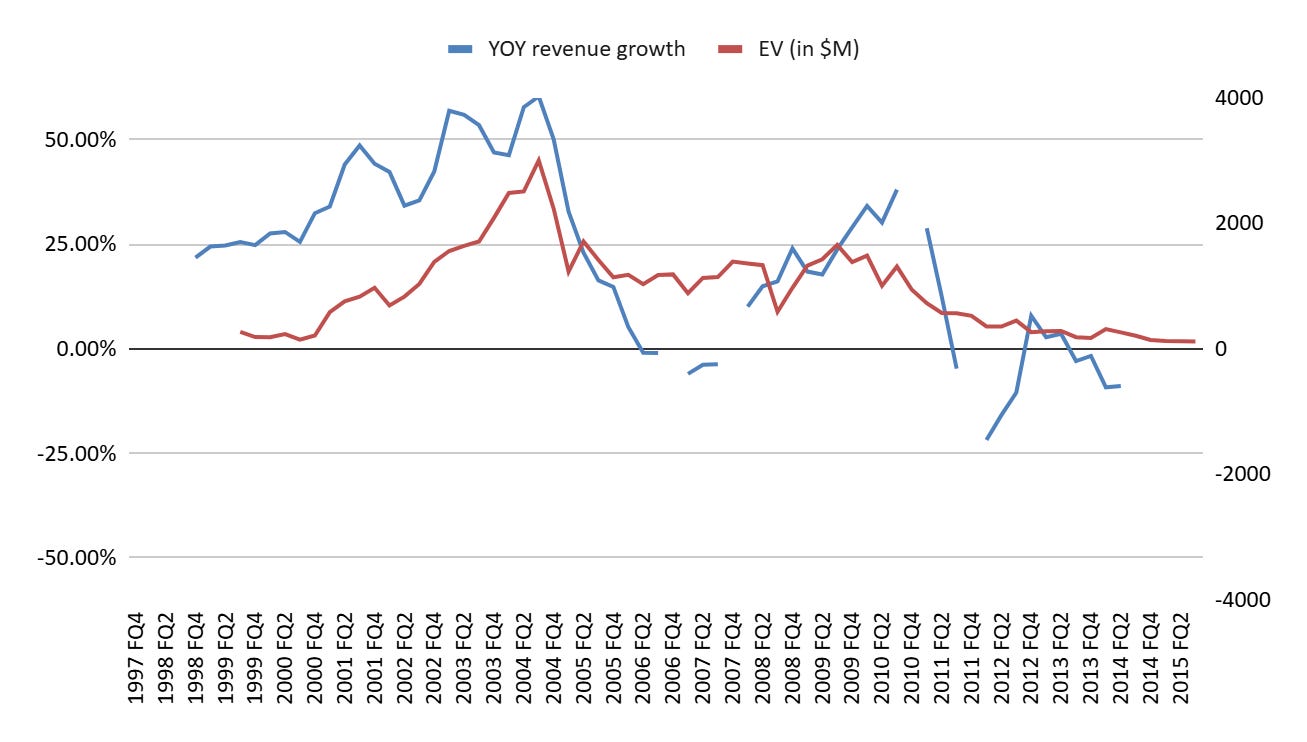

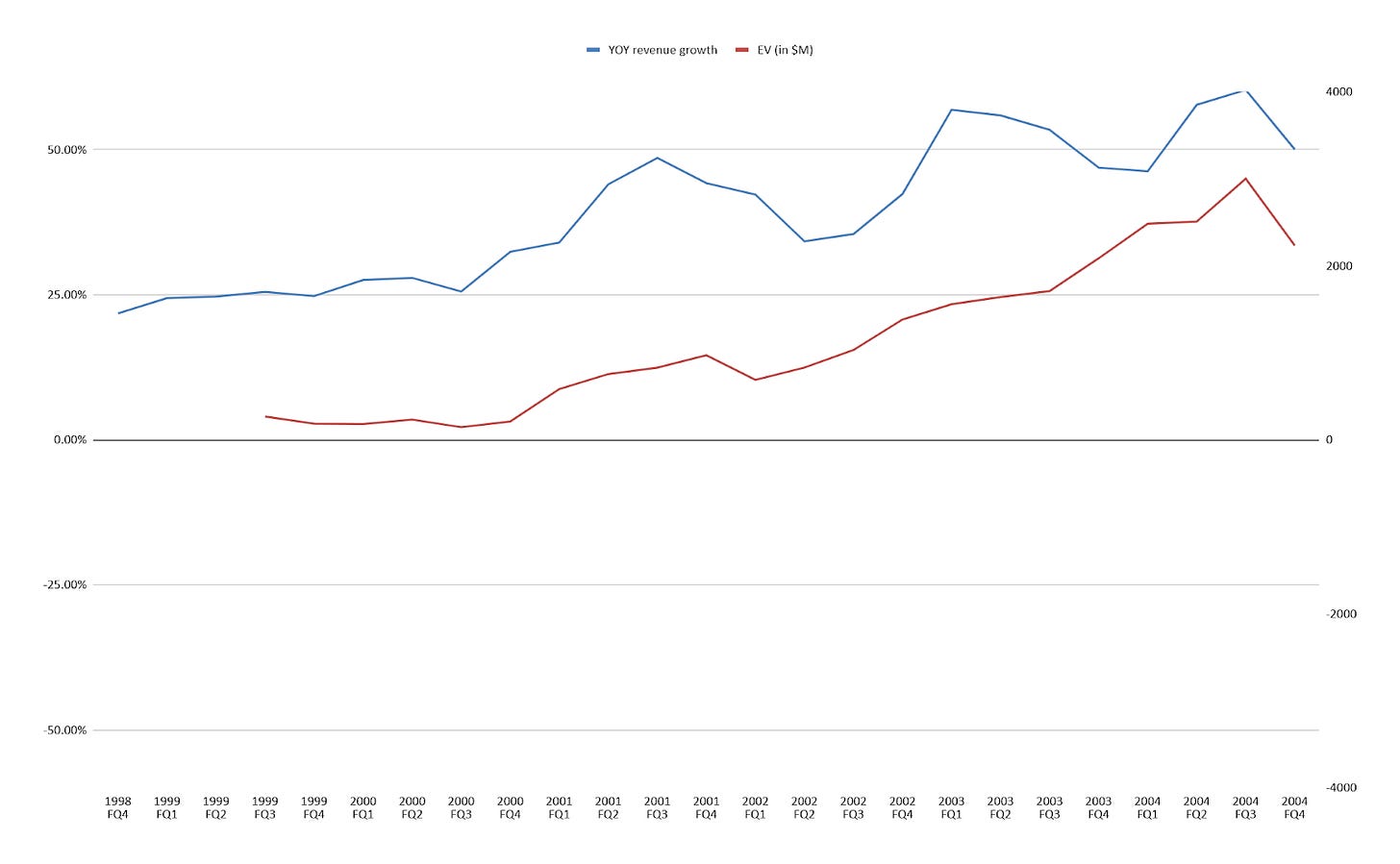

Corinthian Colleges is a prime example of these cyclical patterns. It was founded in 1995 and went public in 1999. From 1999 to 2010 it bought 85 colleges and acquired 33. By 2010, it had 118 schools, $1.8B in revenue growing at 30% YoY and operating income by 180% YoY. And 5 years later it was bankrupt.

The corporate history of Corinthian Colleges has 4 phases. Growth (1999-2004), Stabilization (2004-2007), Recession (2007-2011), Death (2012-2015).

All COCO financial data from S&P Global. Unfortunately a few years are missing.

Growth (1999-2004)

Corinthian went public in 1999 with the express purchase of acquiring and improving for-profit schools. Naturally, during these early years, Corinthian College grew its campuses at a decent clip, typically at ~10x EBITDA, while also increasing attendance at its older campuses.

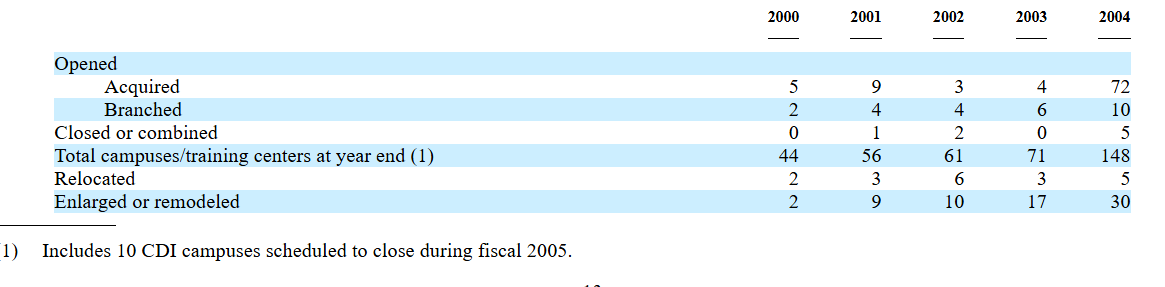

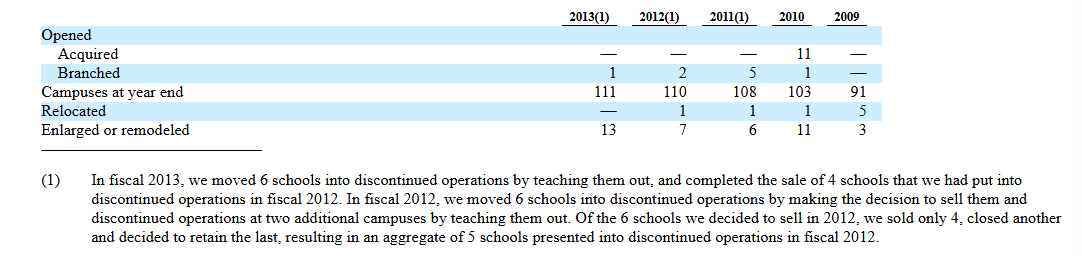

Campus changes

On January 18, 2000, we acquired substantially all of the assets of Harbor Medical College, which operated one college in Torrance, California, for approximately $300,000 in cash.

On April 1, 2000, we acquired substantially all of the assets of the Georgia Medical Institute, which operated three colleges in the greater Atlanta, Georgia metropolitan area, for approximately $7.0 million in cash.

On June 1, 2000, we acquired substantially all of the assets of Academy of Business College, Inc. which operated one college in Phoenix, Arizona, for approximately $1.0 million in cash.

On October 23, 2000, we acquired substantially all of the assets of Educorp, Inc. which operated four colleges in California, for approximately $12.6 million in cash.

On November 1, 2000, we acquired substantially all of the assets of Computer Training Academy, Inc. which operated two colleges in northern California, for approximately $6.1 million in cash. We closed one campus in April 2002 and combined the second campus with another campus in close proximity in June 2004.

On February 1, 2001, we acquired all of the outstanding stock of Grand Rapids Educational Center, Inc., which operated three campuses in Michigan and Illinois, for approximately $2.8 million in cash.

On April 1, 2002, we acquired all of the outstanding stock of National School of Technology, Inc., which operated three campuses in the greater Miami, Florida area, for approximately $14.4 million in cash.

On July 1, 2002, we acquired all of the outstanding stock of Wyo-Tech Acquisition Corporation, which operated two colleges in Laramie, Wyoming and Blairsville, Pennsylvania. The cash purchase price was $84.4 million and was funded through cash on hand and approximately $43 million provided from our credit facility. [This purchase price was 9.5x EBITDA

On January 2, 2003, we acquired substantially all of the assets of Learning Tree University, Inc. and LTU Extension, Inc., which operated two training centers in southern California, for approximately $5.3 million in cash of which $2.0 million was deferred subject to achieving certain operating performance criteria. We closed the two LTU training centers in May 2004.

On August 1, 2003, we acquired all of the outstanding stock of Career Choices, Inc., which operated 10 campuses in California, Washington and Oregon, for approximately $56.3 million, financed through a combination of available cash and borrowings from our credit facility. We combined one of the campuses in Washington with other campuses in close proximity in June 2004.

On August 6, 2003, we acquired substantially all of the assets of East Coast Aero Tech, LLC, which operated one campus in Massachusetts, for approximately $3.2 million plus or minus certain balance sheet adjustments, financed through a combination of available cash and borrowings from our credit facility.

On August 19, 2003, we acquired approximately 89% of the outstanding shares of common stock of CDI Education Corporation (“CDI”) through a tender offer to acquire all of the outstanding shares of common stock. As of October 7, 2003, we had acquired all shares of CDI for approximately $42.1 million and the assumption of approximately $10 million of debt and other liabilities. We funded the acquisition with available cash and borrowings from our credit facility. CDI operated 45 post-secondary colleges and 15 corporate training centers throughout Canada. In October 2003, we completed the acquisition of CMA Careers, Inc. located in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada. The intent to acquire this campus by CDI had been agreed to prior to our acquisition of CDI. We combined one of the CDI campuses with another campus in close proximity in April 2004. Subsequent to year ended June 30, 2004, we announced the expected closing of 10 campuses during fiscal 2005.

Effective August 4, 2004, subsequent to year end, we acquired substantially all of the assets of AMI International Training Center (“AMI”) for approximately $11 million, plus the assumption of certain liabilities of approximately $0.5 million. We funded the acquisition with available cash. AMI operates one campus in Daytona Beach, Florida that offers accredited diploma programs to prepare students for jobs as motorcycle, marine, and personal watercraft technicians. AMI’s specialized motorcycle technician and dealership management programs prepare students for positions with well-known dealerships such as BMW, Harley-Davidson, Ducati, Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki, Triumph, and Yamaha. AMI had approximately 210 students as of July 30, 2004.

By 2005, Corinthian had 148 campuses, including 10 campuses in Canada scheduled to close during fiscal 2005, and 15 training centers, with more than 64,800 students, in 22 states and 7 Canadian provinces.

Key financials (2004)

Revenues $804,283

Gross profit: $385,003

Operating income: $135,290

Gross margin 47.8%

Operating margin , 16.8%

Diluted shares out 94.2M

EV $2.2B

EV/EBIT LTM 17

EBIT Growth 15%

Regulatory Updates

Federal Funding: Approximately 81.0% of the company’s revenues (on a cash basis) were derived from federal Title IV financial aid programs in fiscal 2004.

90/10 Rule: No institution received more than 90% of its revenue from federal student aid programs in fiscal 2004; the highest was 86.5%.

Financial Responsibility: For fiscal 2004, all schools exceeded the DOE’s requirements for financial responsibility, with composite scores ranging from 1.8 to 3.0. The company’s consolidated score was 2.07.

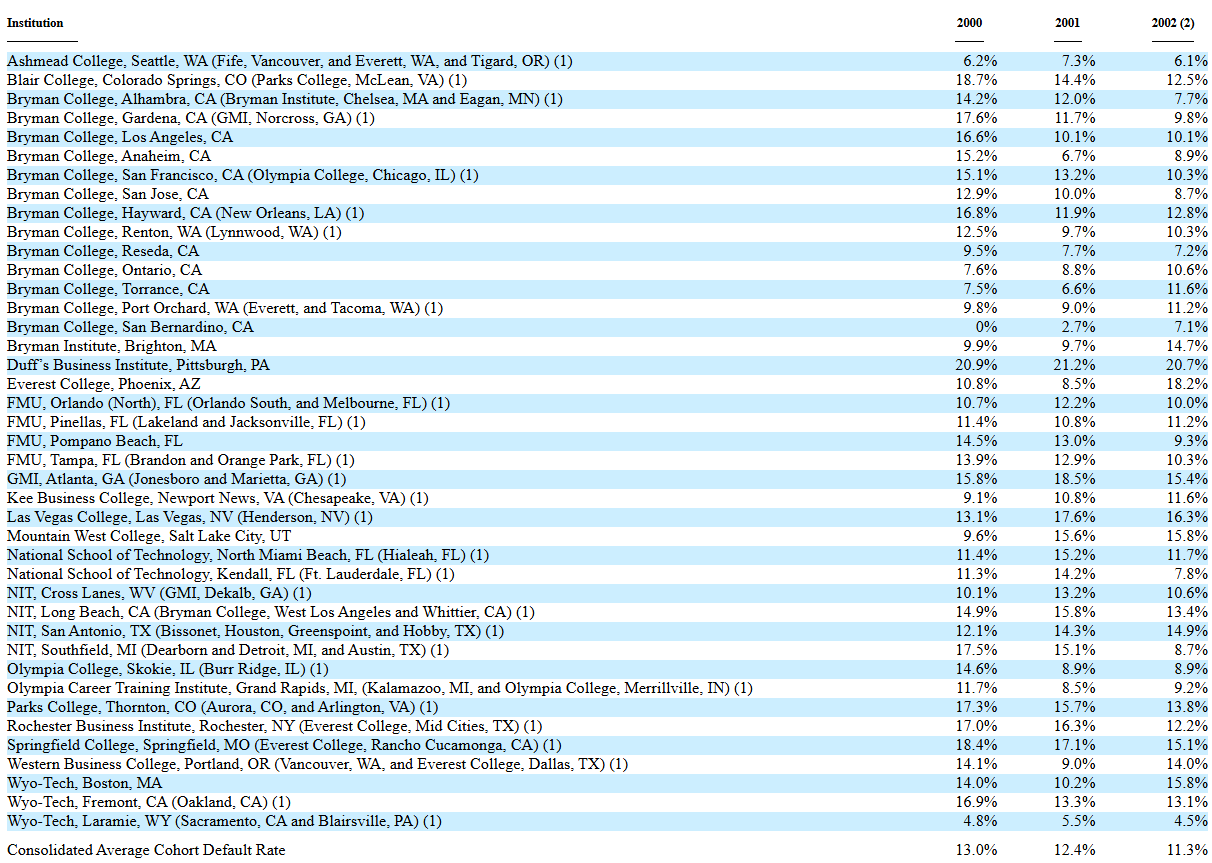

Cohort Default Rates: For federal fiscal year 2001 (the last year with final published rates), default rates for Corinthian institutions ranged from 2.7% to 21.2%. An institution may lose eligibility if its rate exceeds 25% for three consecutive years. Additionally, twelve institutions had Perkins program default rates over the 15% threshold for the 2002 award year.

Legal Updates

Notable legal proceedings during this period included:

A putative class action lawsuit (Montoya v. Corinthian Schools, Inc.) was filed by a former instructor alleging that instructors were improperly classified as exempt from California’s overtime laws.

Three putative class action lawsuits were filed by current and former students of Florida Metropolitan University (”FMU”) alleging that FMU concealed its accreditation status and that its credits were not transferable to other institutions.

In 2004, various putative class action lawsuits were filed against the company and certain executives, alleging material misrepresentations and failure to disclose material facts about the company’s business, causing inflated stock prices.

In July 2004, company representatives voluntarily met with the California Attorney General’s office and provided information regarding three previously settled lawsuits.

A Qui tam lawsuit by a former employee was filed later in 2004, but the DOJ declined to intervene.

Corporate Restructuring and Strategy Shift (2005-2007)

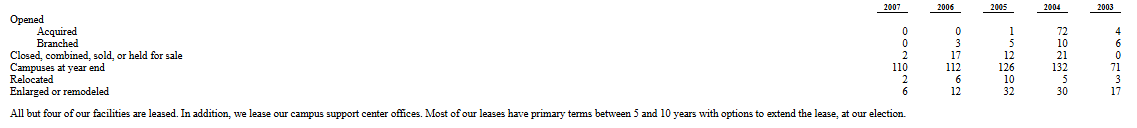

As of June 30, 2007, Corinthian Colleges operated 110 schools in 24 states and Ontario, Canada, with a student population of over 62,115. The company’s facilities totaled approximately 4.8 million square feet.

From fiscal year 2005 to 2007, Corinthian Colleges began to run into issues with integrating its recent acquisitions, and began seeing brand image tarnishment due to its aggressive sales practices and associated lawsuits. During this period, the company shifted its strategy from rapid acquisition-based growth to focusing on operational efficiency and brand consolidation. The company significantly slowed its acquisition activity and new branch openings to better utilize the capacity it had built in previous years.

Divestitures:

In November 2005, the company completed the sale of its corporate training division, CDI Education, which operated 14 locations in Canada.

By the end of fiscal 2005, the company had closed 11 CDI campuses and one training center in Canada as part of a “teach-out” process that began in July 2004.

During the fourth quarter of 2007, Corinthian decided to divest all CDI campuses located outside of Ontario, Canada, as well as the WyoTech campus in Boston. These locations were classified as “held for sale,” with the sales expected to be completed in fiscal 2008.

Branding: The company began consolidating its various school brands under two national names: Everest and WyoTech. As of June 30, 2007, 65 of the company’s 110 schools were operating under the Everest brand and seven under the WyoTech brand. This process led to an impairment charge of $4.5 million in the fourth quarter of fiscal 2007 for trade names that would no longer be used.

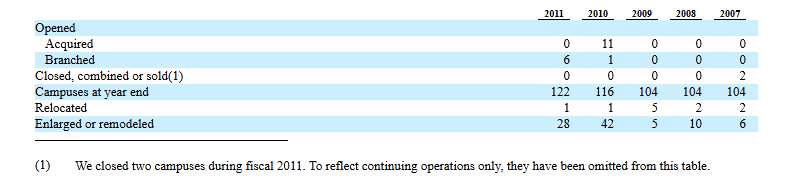

Campuses:

Key financials (2007)

Revenues $919,224

Gross profit: $385,229

Operating income: $26,198

Gross margin 41.8%

Operating margin 2.7%

Diluted shares out 85.8M

EV $1.4B

EV/EBIT LTM 37

EBIT Growth -40%

Regulatory Update

Federal Funding: In fiscal year 2007, approximately 75.2% of the company’s revenues (on a cash basis) came from federal Title IV financial aid programs.

90/10 Rule: All institutions complied with the requirement that no more than 90% of revenue comes from federal aid; the highest institution received 87.2% of its revenue from these programs.

Financial Responsibility: For fiscal 2007, all schools met the U.S. Department of Education’s (ED) financial responsibility standards, with composite scores ranging from 1.5 to 3.0. The company’s consolidated score was 1.7.

Cohort Default Rates: For federal fiscal year 2004 (the last year with final data), student loan default rates for Corinthian institutions ranged from 3.7% to 17.5%. Additionally, 11 institutions had Perkins program default rates above the 15% threshold for the 2005 award year.

Accreditation Issues: As of June/July 2007, four campuses were under heightened scrutiny from accreditors:

Everest College in San Francisco, CA was placed on

probation by its accreditor (ACCSCT).Everest Institute in Houston, TX was placed on

probation by its accreditor (ACCSCT).NST campuses in Miami and Hialeah, FL received a

Show Cause order from their accreditor (ABHES).In total, 20 colleges were on “reporting” status with their accrediting agencies, primarily concerning student completion and placement rates.

Legal Update

Corinthian faced several significant legal and regulatory challenges during and prior to 2007. The company established an aggregate reserve of approximately $7.2 million for all disclosed legal matters as of June 30, 2007.

In 2005, The education department completed a report finding misrepresentation to students, breaches of fiduciary duty, intentional evasion of 90/10 requirements. Steve Eisman launched a short campaign here.

California Attorney General (CAG): An investigation that began in June 2004 was settled on July 31, 2007. Without admitting wrongdoing, Corinthian agreed to a settlement totaling approximately $6.5 million, which included payments and debt forgiveness for former students. The company also agreed to stop enrolling students in 11 programs at nine California campuses.

Florida Attorney General (FL AG): An investigation into Florida Metropolitan University (”FMU”) was resolved on August 21, 2007. The company denied any wrongdoing and made an immaterial payment to the FL AG’s office; no fines or restitution were required.

Securities Class Action: A consolidated class action lawsuit filed in 2004 alleging material misrepresentations was dismissed by the district court in April 2006. However, the plaintiff appealed the dismissal to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Student Lending Inquiries: The Attorneys General of Illinois and Arizona requested information from the company regarding its relationships with private student loan providers as part of broader inquiries into student lending practices.

Stock Option Review: A review by the SEC into the company’s historical stock option grants, which began in August 2006, was completed in July 2007. The SEC staff recommended no enforcement action. This review led to several derivative lawsuits against current and former directors and officers, which were consolidated in state and federal courts.

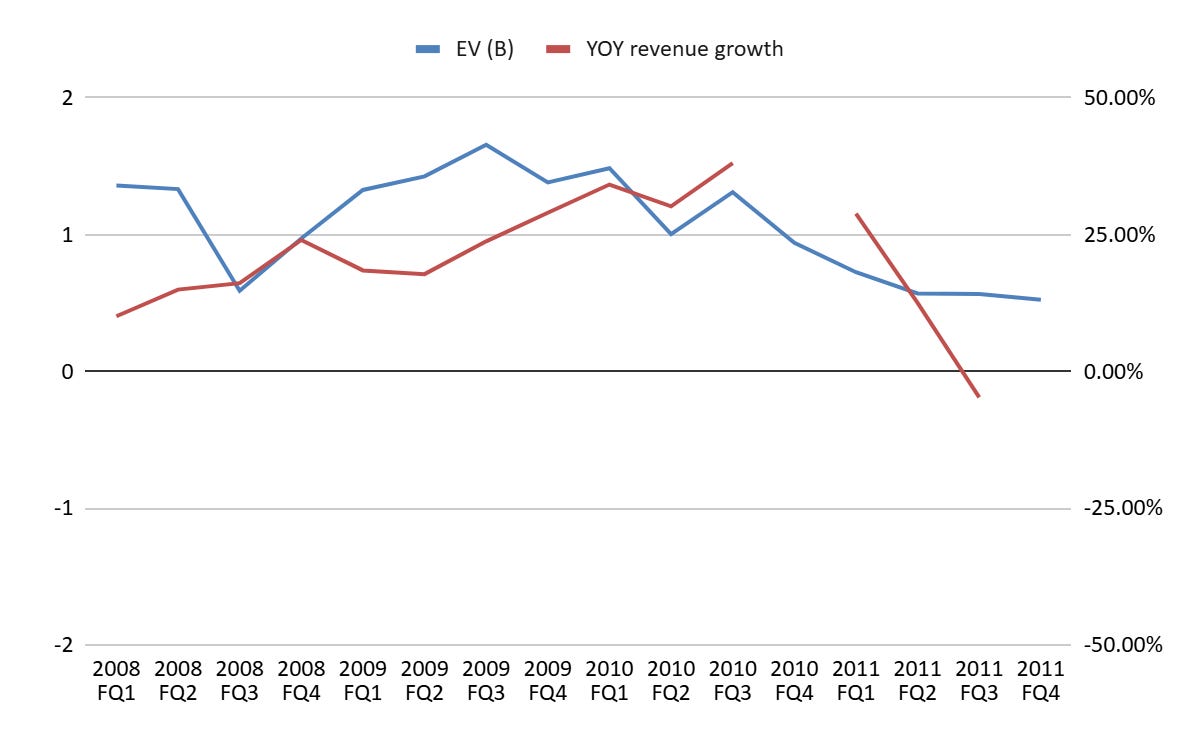

Growth, Acquisitions, and Restructuring (2008-2011)

As of June 30, 2011, Corinthian Colleges operated 122 schools across 26 states and Ontario, Canada, with a total student population of 93,457. Online education was a significant growth area, with student course registrations increasing by 27% in fiscal 2011 and serving approximately 26,100 exclusively online students.

During this period, Corinthian Colleges shifted from organic growth to a major strategic acquisition, while also divesting several campuses. The company significantly expanded its student loan programs to fill funding gaps left by the changing private loan market.

Heald College Acquisition: On January 4, 2010, Corinthian acquired Heald Capital, LLC (”Heald”) for $395 million in cash. Heald operated 12 regionally accredited campuses, adding approximately 17,566 students as of June 30, 2011. The acquisition was funded with existing cash and $224 million in borrowings. [This was 9.5x Adj. EBITDA]

Divestitures:

In February 2008, the company sold 12 Canadian schools located outside of Ontario.

In May 2008, the company completed the sale of the WyoTech Boston campus.

Organic Growth: After a pause, the company resumed expansion by opening one new branch campus in fiscal 2010 and six new branch campuses in fiscal 2011.

Private Loan Programs:

In fiscal 2008, after private lenders like Sallie Mae stopped offering subprime loans, Corinthian created a new “discount loan” program with Genesis Lending Services, Inc. (”Genesis”). Under this program, Corinthian acquired the loans and assumed the credit risk.

On June 29, 2011, Corinthian entered into a new agreement with ASFG, LLC (”ASFG”) to fund approximately $450 million in new student loans over the next two years. Under this program, Corinthian is obligated to repurchase any loan that becomes over 90 days delinquent.

Campus Changes:

In 2010 Corinthian acquired Heald Capital, LLC

Key financials (2011)

Revenues $1,784,000

Gross profit: $737,557

Operating income: $143,491

Gross margin 41.25%

EBIT margin 7.87%

Diluted shares out 84.7M

EV $525M

EV/EBIT LTM 4

EBIT Growth -33%

Goodwill Impairment: In the second quarter of fiscal 2011, the company recorded a goodwill impairment charge of $203.6 million due to a decline in its market capitalization below its book value, driven by regulatory uncertainty.

Regulatory Update

The 2008-2011 period was marked by a dramatic increase in regulatory oversight and new rulemaking by the U.S. Department of Education (ED) and Congress, which significantly impacted the entire for-profit education sector.

New ED Regulations (2010-2011): The ED introduced sweeping “program integrity” rules, with the most significant being:

Gainful Employment: New rules effective July 1, 2012, require educational programs to meet specific debt-to-income and loan repayment rate metrics to remain eligible for Title IV funding. Programs that fail for three out of four years will lose eligibility. The company noted it could not predict which programs would fail but expected downward pressure on tuition and potential limits on enrollment.

Incentive Compensation: The elimination of 12 “safe harbors,” effective July 1, 2011, broadly prohibits basing employee compensation, in any part, on success in securing student enrollments. This forced the company to change its compensation practices for admissions and other staff.

Increased Scrutiny:

Starting in 2010, Corinthian became the subject of investigations and document requests from the Attorneys General of

Florida, California, Massachusetts, New York, and Oregon regarding its business practices.The Senate HELP Committee launched a series of hearings and broad information requests to approximately 30 for-profit education companies, including Corinthian, starting in June 2010.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) conducted an undercover investigation that included two Corinthian campuses and issued a report in August 2010 that characterized some recruiting practices as “deceptive or otherwise questionable,” a characterization Corinthian disputed.

Federal Funding (90/10 Rule): For fiscal 2011, approximately 80.2% of the company’s U.S. revenue was derived from Title IV funds under temporary relief rules. Without that relief, the figure would have been

88.5%, with nine institutions exceeding the 90% threshold. To ensure compliance, the company delayed drawing down $87.0 million in Title IV funds at the end of fiscal 2011.Accreditation Issues:

Everest College Phoenix was placed on probation by its accreditor (HLC) in May 2009, and this was elevated to a “Show-Cause Order” in November 2010, requiring the school to prove why its accreditation should not be removed. A final decision was pending a November 2011 board meeting.

Everest Institute in Decatur, GA was also placed on a “Show Cause” order by its accreditor (ACCSC) in December 2010 for failing to meet student achievement outcomes.

As of June 30, 2011,

25 colleges were on “reporting status” with their accrediting agencies, primarily for student completion and placement rates.

Legal Update

Intensified regulatory scrutiny coincided with a wave of new litigation from shareholders and students.

Securities Litigation: A new putative class action lawsuit was filed on August 31, 2010, against the company and several current and former officers, alleging material misrepresentations about the business between 2007 and 2010. This was followed by related shareholder derivative complaints.

Qui Tam (False Claims Act) Lawsuits: Of three lawsuits filed in 2007 alleging improper admissions compensation practices, two were dismissed. However, in August 2011, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the dismissal of the third case (

U.S. ex rel. Lee v. Corinthian) and sent it back to the district court, allowing the plaintiff to amend their complaint.Student Class Actions: The company faced an “unprecedented increase” in putative class action lawsuits by former students during fiscal 2011. These lawsuits, filed across the country, generally alleged misrepresentations regarding accreditation, transferability of credits, and job placement outcomes, often citing the ongoing government hearings and investigations. The company’s legal strategy was to compel these cases into individual arbitration based on enrollment agreements.

Later in 2010, the company was subpoenaed by the state attorney general of Florida, California, New York, Oregon and Illinois. Around this time they also received negative comments from one of its accreditors, closing 10 campuses.

Restructuring and New Student Loan Program (2012-2013)

As of June 30, 2013, Corinthian operated 111 schools in 25 states and Ontario, Canada, with a student population of 81,284, a decrease of 10.5% from the prior year. The decline was largely attributed to the elimination of federal aid for new “Ability to Benefit” (ATB) students who lack a high school diploma. Online education remained a key area, serving approximately 27,740 students.

During this period, Corinthian Colleges focused on managing its existing schools rather than expansion. The company continued to divest underperforming campuses and launched a new, large-scale private student loan program to ensure students had access to funding.

Campus Divestitures and Closures:

In fiscal year 2013, the company completed the “teach-out” (closure) of six campuses across the U.S. and Canada, including locations in Arlington, VA; Decatur, GA; and London, Ontario.

Also in fiscal 2013, Corinthian completed the sale of four Everest schools in California to BioHealth College, Inc., paying the buyer $2.3 million to assume operations.

The WyoTech campus in Sacramento, CA, was taught out after a sale did not materialize.

Acquisition: In August 2012, Corinthian acquired QuickStart Intelligence Corporation, an IT corporate training company, for $13.3 million in cash. The primary goal was to adopt QuickStart’s short-term courses to provide additional non-Title IV revenue sources to help schools comply with the 90/10 rule.

New Student Loan Program:

During the second quarter of fiscal 2012, the company fully transitioned to a new private loan program managed by ASFG, LLC (now Campus Student Funding, LLC).

The agreement with ASFG commits the firm to purchase up to $775 million in new student loans through June 2015.

Under the program, Corinthian is obligated to repurchase any loan that becomes over 90 days delinquent, exposing the company to significant credit risk. Total losses on these loans are estimated to be approximately 50% of the amount funded.

Campus Changes

Key financials (Q3 2013-Q2 2014)

Revenues $1,514,000

Gross profit: $587,420

Operating income: $36,561

Gross margin 38.77%

EBIT margin 2.37%

Diluted shares out 88M

EV $261M

EV/EBIT LTM 7

EBIT Growth -50%

Regulatory Update

Intense regulatory scrutiny from federal and state agencies continued to define Corinthian’s operating environment, with a particular focus on student outcomes, financial responsibility, and recruiting practices.

Intensified Investigations:

Since October 2010, the Attorneys General of eight states, including California, Florida, Massachusetts, and New York, have requested extensive documents regarding the company’s business practices.

In June 2013, the

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began an investigation, requesting documents related to student recruitment, attendance, placement, loan defaults, and compliance with Department of Education (ED) financial rules.In April 2012, the

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) served the company with a Civil Investigative Demand to determine if it was engaging in unlawful practices related to private student loans.ED’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) subpoenaed the company’s Jonesboro, GA campus regarding employment and placement rates in April 2011. This matter is being supervised by an Assistant U.S. Attorney focused on False Claims Act cases.

Financial Responsibility Score:

On August 16, 2013, the ED notified Corinthian that its fiscal 2011 “composite score” was 0.9, below the 1.0 minimum, largely due to ED treating a $203.6 million goodwill impairment as an operating expense. A score below 1.0 can trigger a requirement to post a letter of credit.

ED determined the company’s fiscal 2012 score was 1.5, meeting the minimum, but stated it was still reviewing certain debt related to the company’s student loan program.

The company’s lenders granted a waiver for the fiscal 2011 score, which could have been considered an event of default under its credit facility.

“Gainful Employment” Rule: The most punitive parts of the rule, which would have tied Title IV eligibility to graduates’ debt-to-income ratios, were struck down by a federal court on June 30, 2012. However, the disclosure requirements remained, and ED announced its intent to re-introduce the rule through a new rulemaking process beginning in September 2013.

90/10 Rule: In fiscal 2013, two of the company’s 37 institutions exceeded the 90% threshold for revenue from Title IV programs. Since it was the first time for these schools, they did not lose eligibility but were placed on provisional certification for two years. Overall, the company derived approximately 84.8% of its net U.S. revenue from Title IV programs.

Cohort Default Rates: The company showed significant improvement in student loan default rates. The draft three-year Cohort Default Rate for the 2010 cohort was 19.0%, a substantial decrease from the 28.0% rate for the 2009 cohort. No institutions exceeded the 30% threshold for the 2010 cohort.

Legal Status

Corinthian continued to face a number of lawsuits from former students, employees, and shareholders.

Qui Tam (False Claims Act) Lawsuit: In a case alleging the company violated the incentive compensation ban, the U.S. District Court dismissed the First Amended Complaint with prejudice on April 12, 2013. The plaintiffs (relators) have since appealed this dismissal to the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Securities Class Action: A class action filed in 2010 alleging misrepresentations about the company’s business was dismissed with prejudice on August 20, 2012. The plaintiffs appealed the dismissal. A new securities class action was filed on June 20, 2013, covering the period from August 2011 to June 2013.

Student Litigation: The company continued to defend against numerous putative class action lawsuits from former students alleging misrepresentations regarding programs, accreditation, and job prospects. Most of the lawsuits filed in fiscal 2011 had been dismissed, but several remained active, with the company seeking to compel them to individual arbitration.

In 2012, the education department began restricting Corinthian’s access to Title IV funds and in 2013, Vice President Harris, then CA attorney general, accused Corinthian of securities and consumer fraud, and won a $1.1 billion judgment three years later (2016).

In 2018, an FTC lawsuit was announced.

Summary

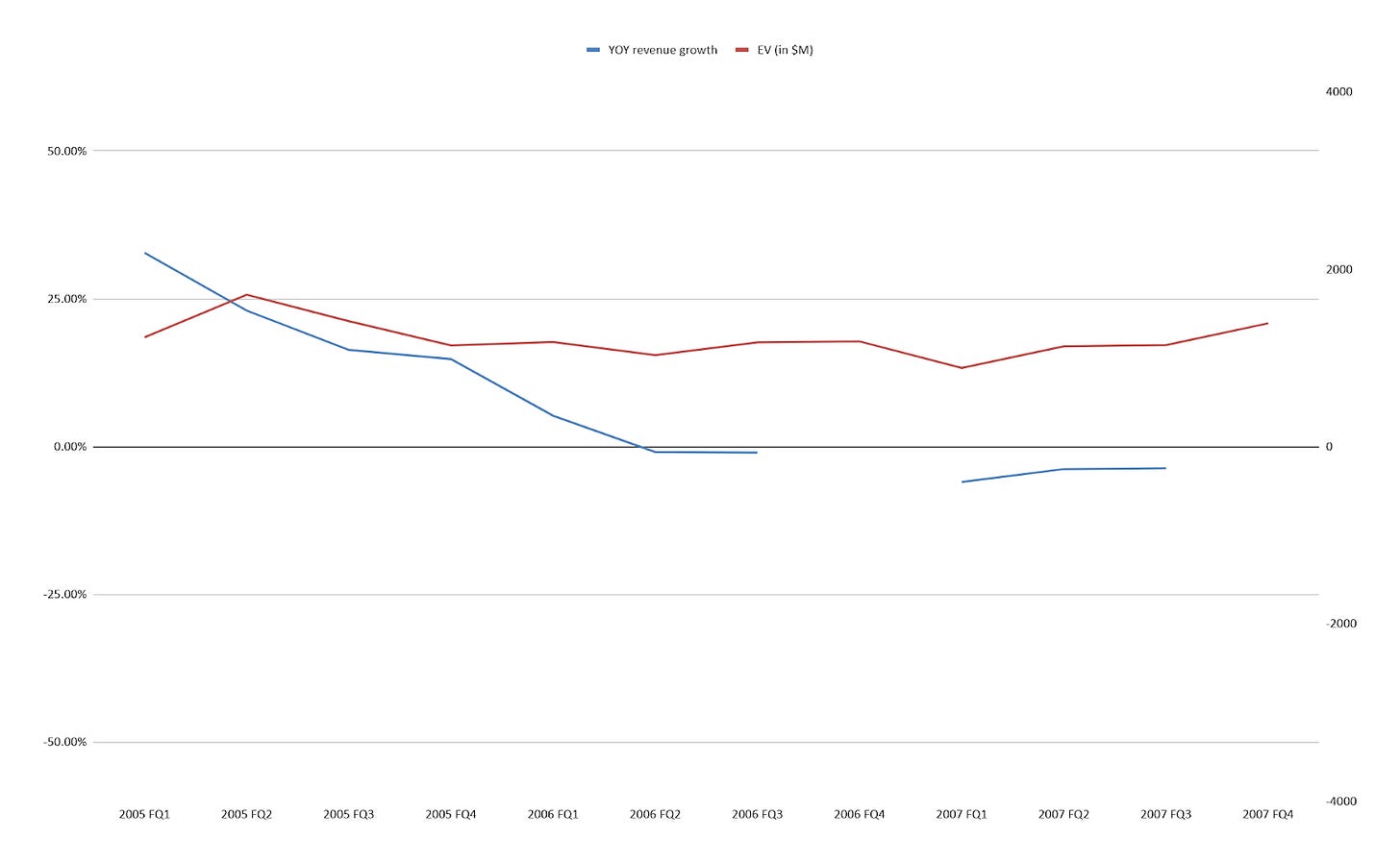

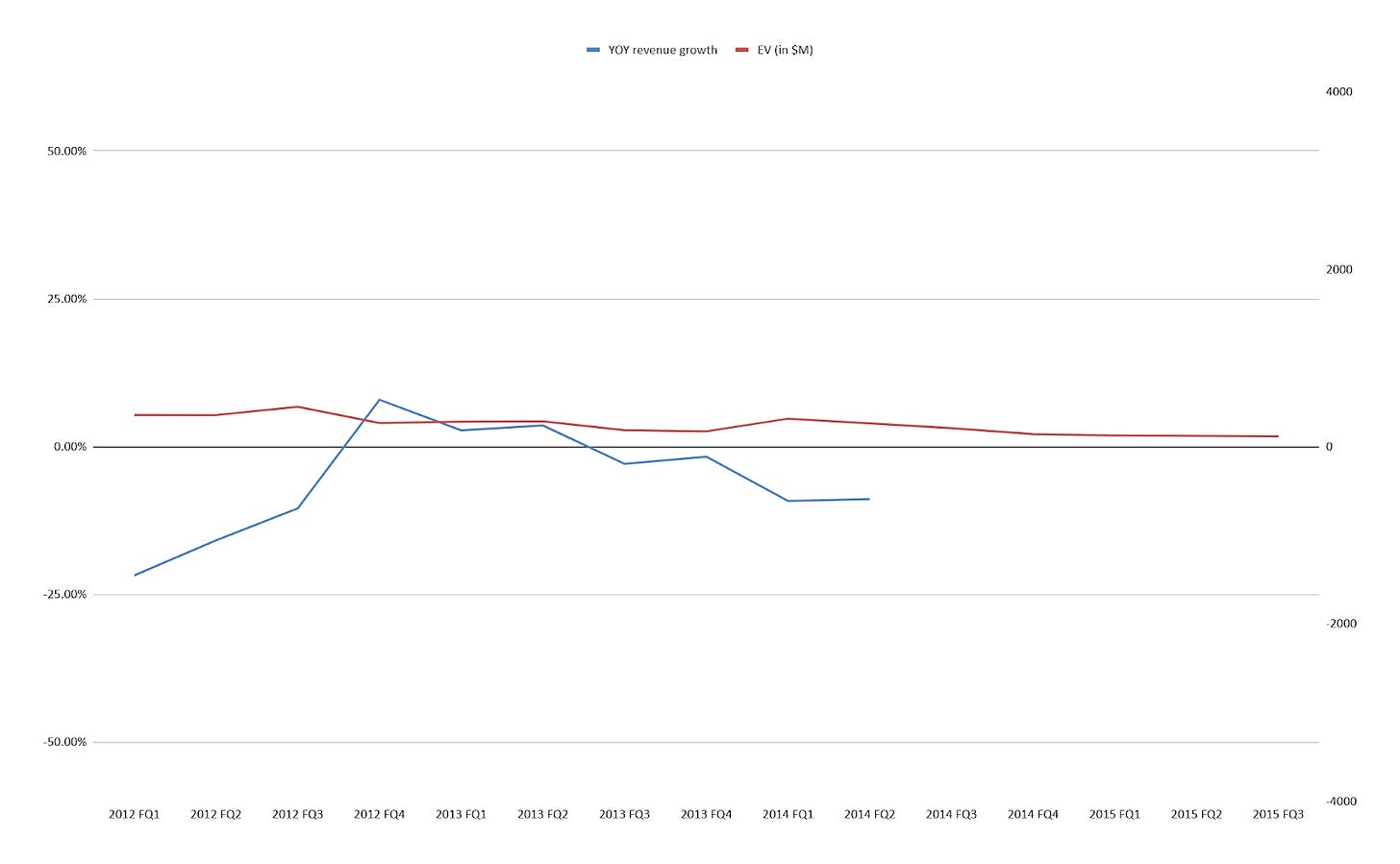

When I consider the rise and fall of Corinthian Colleges, I see 2 interesting inflection points. The first is the end of the growth narrative. Once growth fell below the historic 30% in Q2 of 2005, the market cap of the company halved. The second moment is the company’s bankruptcy, when the equity value went to 0. An understanding of these moments and the quarters preceding them is key to be able to understand the downside risks of this industry.

Inflection Point 1: The End of Growth — Why Did Growth Stop, and Could We Have Seen It Coming?

Corinthian’s first major inflection point came in Q2 2005, when revenue growth slipped below its historical 30% trajectory. On the surface, the company was still expanding, but the underlying economics had already begun to break down. The easy growth of the early 2000s—driven by acquisitions, rapid campus openings, and aggressive enrollment tactics—was no longer sustainable.

Declining enrollment growth vs. higher advertising / recruiting spend

Enrollment peaked in the mid-2000s (roughly ~64.8k students reported around FY2004) while corporate marketing and admissions spending increased. This indicated that new enrollments were harder to acquire, that there was diminishing incremental yield per marketing dollar.

That’s why key metrics in this industry include quarterly marketing & recruiting spend / net new students (CAC per enrolled student) and marketing & recruiting spend / revenue.

In COCO’s case, CAC per enrolled student was rising >20% YoY while enrollment growth fell below management’s historical target ( <30%). Marketing/recruiting spend as a percent of revenue rising 2-3% YoY was also a warning.

Rising dependence on Title IV (approaching the 90/10 cap)

In the early 2000s Corinthian’s Title IV share of revenue was already very high (~81% in FY2004) and some campuses reported 85–87%+ at times. Filings around this time show management delaying draws at year-end to stay under the 90% test—an administrative sign of constraint.

A key metric to look out for is Title IV receipts / total revenue companywide and by campus every filing period, and always monitor the 90/10 calculation notes in MD&A. Is the calculation getting more generous, etc.

Early lawsuits and multi-state AG investigations (reputational/regulatory signalling)

By 2004–2005 Corinthian was the subject of multiple state investigations and student class actions (e.g., inquiries from California and Florida AG offices). These early legal actions were not yet massive dollar events, but they were a clear sign of systemic recruiting problems.

Litigation and AG attention are high-signal: they predict future regulatory scrutiny, accreditors’ actions, and borrower claims (BDR).

An analyst should always scan company 8-K filings for legal updates, read the legal-proceedings note in 10-K, and note any related state AG press releases. Are investigations single-state vs. multi-state? Also look out for material increases in legal reserves (+1-2% of revenue)

Accreditation warnings, show-cause orders, and program closures (quality erosion)

Starting in mid-2000s, a growing number of COCO campuses moved onto “reporting” status with accreditors; over the next few years some campuses received probation or show-cause notices for low completion/placement rates. Accreditation problems began to show as early warning notes in filings and accreditor communications.

An analyst should always review accreditor notices, the 10-K accreditation section, and campus-level disclosures (transferability, placement metrics). Track the count of campuses in “reporting/probation” status, and where they end up. Look out for any campus on probation or show-cause; >10% of campuses in reporting status; accreditors requesting teach-outs or program suspensions.

Inflection Point 2: The End of the Company — Why Did It Fail, and Could We Have Seen It Coming?

The second inflection point came in the years leading up to Corinthian’s 2015 bankruptcy. By that point, the company had lost the confidence of its regulators, accreditors, and investors. The same forces that fueled early growth now became liabilities.

As scrutiny intensified, the Department of Education placed Corinthian under heightened cash monitoring, delayed Title IV disbursements, and eventually froze funding altogether. The company’s financial responsibility composite score fell below the 1.0 threshold in 2013, signaling distress. In parallel, lawsuits and settlements eroded liquidity and investor trust. The company’s pivot to self-financed private loan programs, where default rates exceeded 50%, was a desperate attempt to replace lost federal cash flow.

The company didn’t fail because demand for education disappeared, it failed because its business model was predicated on regulatory tolerance and an unsaturated end market. When either disappears, the economics of the model collapse.

An analyst should be tracking a Composite Score < 1.5 or increasing letters of credit. Take note of increasing Provisional Program Participation Agreements (PPAs) and probationary accreditation. Track mounting legal reserves. Measure exposure to private student loans or loan buyback obligations. Check for any federal funding delays or restrictions.

In this case, once federal funds slowed and the Department of Education signaled noncompliance, Corinthian’s fate was sealed. The company could not survive without access to Title IV funding, and no private market would refinance it under those conditions. And yet at each step equity investors remained optimistic, far into these mounting regulatory pressures.

Conclusion

The for-profit education industry can look attractive at times, but as Corinthian’s story shows, high returns are transient. Eventually one or more of those cycles turns, and tailwinds at your back quickly turn against you.

Corinthian’s collapse shouldn’t be a surprise. It was due to occur, because for-profit colleges live and die by three forces: macro-economics, competition and regulatory action. A wise analyst must analyze all three of these forces to understand this industry.

I hope this write up provides you with a better understanding of the for-profit industry at the company level. I always find post-mortems of failed companies very illustrative of the downside risks to be aware of, and perhaps for a few of you, it might lead to some attractive short opportunities as you notice similar leading indicators of a firm’s decline and collapse in the future.

Very good post! But I think narrowing down on one company isn’t the right approach because there were obviously issues with debt and prevalence of predatory practices and they were just waiting to be sued. Companies like PRDO have also existed in the 90s but they are fine today. I am invested heavily in LGCY so thanks this gives me some metrics to look at and red flags to track