Why do most money managers fail to beat the index?

If one wants to outperform, one should invert.

I recently published an article “5 Active Money Managers who Beat the S&P 500 Index.” It was difficult to find fund managers who met this criteria, I think it is an interesting question to ask why.

The stiffest competition that you could compare yourself to as an active money manager is the S&P500. With the S&P you can own a piece of the top 500 publicly traded American business, and so you are entitled to their future cash flows. It is a bet on the rising average productivity of the overall American economy. It's a good bet. It's one that Buffett recommends for 90% or more of investors. It’s performed very well historically, and is by definition diversified, reducing your risk as an investor.

"In my view, for most people, the best thing to do is to own the S&P 500 index fund," - Buffett

"Most institutional and individual investors will find the best way to own common stock is through an index fund that charges minimal fees."- Buffett

From 1928 through 2023, the S&P 500 annualized nominal return (including reinvested dividends) is ~10% per year. This 10% is nominal, not including inflation or fees. After factoring in 3-4% inflation, real returns average closer to 6–7% historically.

However, beating the index is incredibly hard. 90% of money managers fail to do so.

I was talking with my Mom about this, and she asked "Why is that?"

3 reasons why money managers fail to beat the index so regularly:

1. Most active money managers run diversified funds. These funds are so diversified (20+ stocks) that they are roughly equivalent to an index fund. However, they also have an annual fee of 0.5-2% on all money under management. For example, if they were to just invest in a snp500 equivalent, fees alone would reduce your gross returns from 10% to 8%.

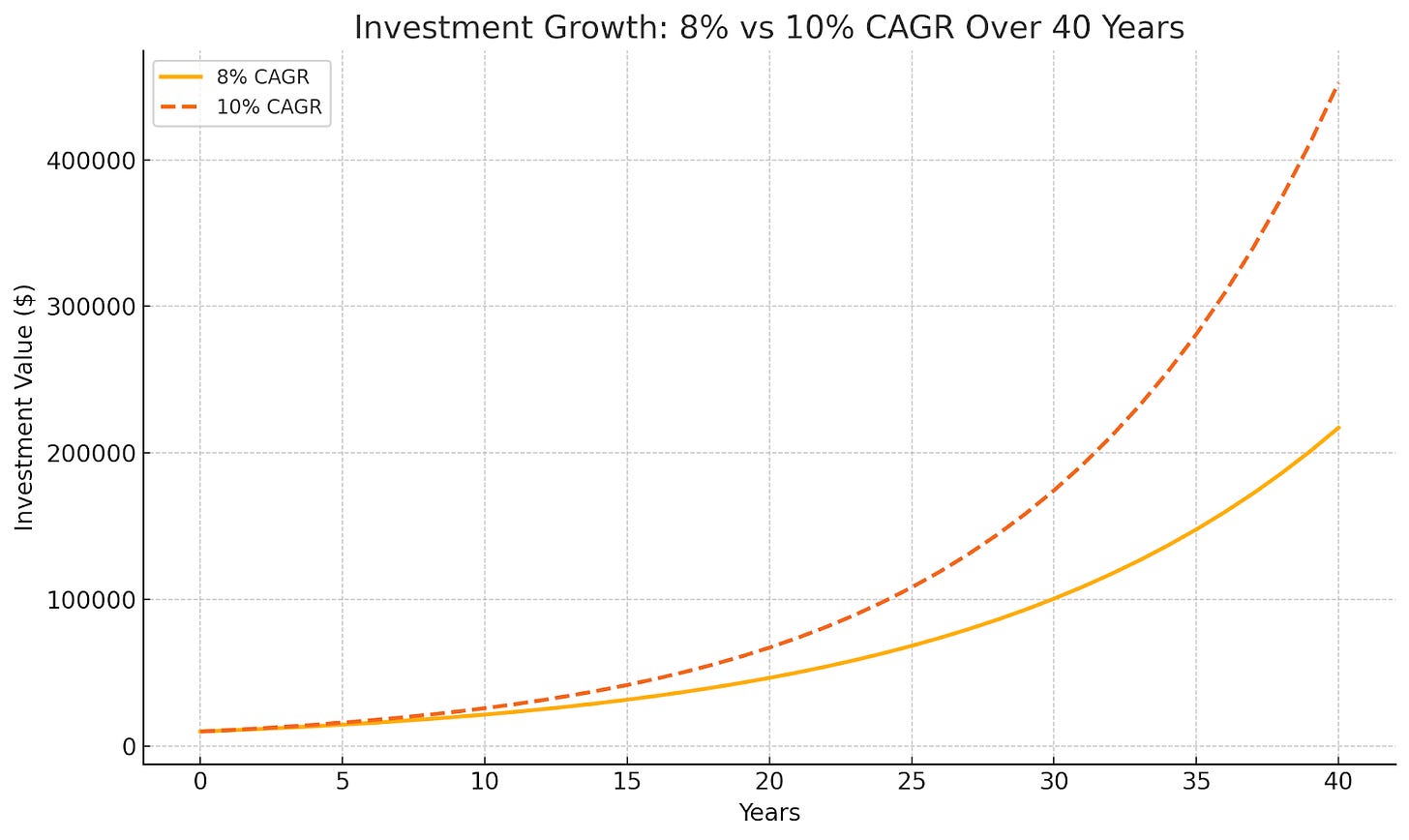

Over 40 years, this creates a huge gap in compounding.

8% CAGR (investing with AUM 2% management fees) : $10,000 grows to $217,245

10% CAGR: $10,000 grows to $452,593

A 2% fee more than halves your final investment value - a strong argument for avoiding high-fee investments and maximizing consistent returns.

This broadly means that any fund that charges AUM fees and that is broadly diversified will not beat the index over any significant period of time.

“Diversification may preserve wealth, but concentration builds wealth.” - WEB

2. Active money managers over manage.

Clients expect money managers to drive high returns. Clients expect that this is done by making many stock purchases, and like to see that their money manager is "busy". After all, the more work done, the higher the return, right? Many money managers oblige (consciously or subconsciously) and buy and sell stock frequently. However, transaction costs are a significant headwind.

Jack Bogle (2014) estimated total transaction costs of 1.44% annually for actively managed funds, broken down as:

0.5%–1.0% from trading costs

0.5%–1.0% from hidden market impact and timing costs

These transaction costs partially exist because the stock market is rigged against traders. On most exchanges, every time you make a trade, you lose a little of your investment, because it is front run by your brokerage who is profiting off of your trade. (This is a major reason why one should not day trade).

It’s a shame that we allow this type of rent seeking on such a massive scale, and people seem to be fine with it. But I digress.

In addition, over the past 10 years, the average actively managed large-cap mutual fund experienced a tax cost of 2.09% annually.

In total these costs add an average of 3.5% in drag on most funds being actively managed.

“It's like Babe Ruth at bat with 50,000 fans and the club owner yelling, 'Swing you bum!” - WEB

3. Over any 10-year period, less than 20% of individual stocks outperform the broad market index. This is the Pareto Principle at work.

An index fund by definition will always include these high performers. If hand-picked funds are created randomly (essentially true), then 80% of these hand picked funds will underperform, because they do not include sufficient concentration in the high performing stocks. This is generally what we see in fund results.

So, let's invert.

If I wanted to find an investor that I was sure would not beat the index, what would I look for?

1. A money manager with a broadly diversified portfolio, and fees that are based on AUM, and not performance.

2. A money manager who trades often. Not holding any given investment for at least one year.

3. OR a money manager who is highly concentrated, but makes the wrong choices.

90% of fund managers fall into one or more of these categories.

What to look for in a money manager

Okay, now let's in-invert (???).

If we wanted to find a successful money manager what would we look for?

1. A money manager with a concentrated portfolio, and fees that are not based on AUM, but on performance.

Michael Burry did not take fees of any kind (I wouldn't expect to find this again).

Warren Buffett only took 25% of any performance he made above 6%, essentially the excess he made above the snp500 benchmark. (Few fund managers choose this route, but the ones that do drive results or starve.) This is the fee structure to look for when choosing a money manager.

2. One that trades infrequently.

I have found that concentrated portfolios tend to force the investor to invest for the long run. If they had to choose a handful of companies, they better be ones that will exist 10 years from now.

3. A money manager who is concentrated, and makes the right choices.

This is easier said than done. But you can see this through historical performance. If you don't have that you can also anticipate this based on their investing philosophy. If they try to buy securities for less than they are worth (value investing) that is a good sign. If they try to understand the business they are investing in deeply, that is essential.

In short, you are looking for someone that has internalized these 4 principles:

1. A stock is part ownership of a business.

2. Price is what you pay, value is what you get.

3. A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. - Aesop

4. The value of a stock is in the cash flows it will produce between now and judgement day (discounted to present value).

Beyond that there are many different temperaments that can do well. Long term investors that understand competitive forces extremely well, for example. Or contrarian investors that can see when the market is pricing a security wrong. There are many paths to value, but a few core principles to look for.

Agree with this. The indices are tough to beat because they are fundamentally a momentum index that always contain the fastest growing stocks. Also, the top companies have been driving a lot of the return, so if you don’t own those, it gets difficult. Not only are they cheaper on fees and trading costs, but they are also more tax efficient. That said, they are getting more concentrated and own things with no regard for valuation.

Well put. But we must also understand that even though these money managers have a long-term mindset and want to concentrate, the money management industry itself doesn't allow them to.

The industry is built to achieve short-term results and continue making money for themselves.