2025 in Review

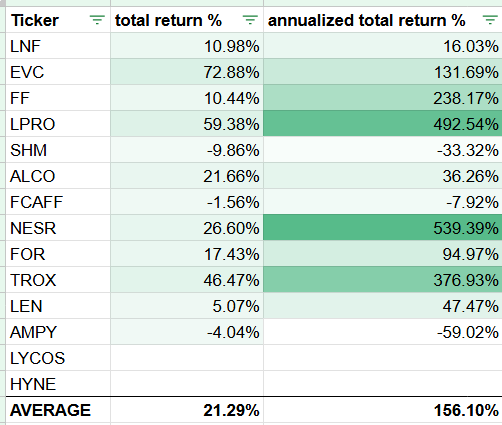

This year, I covered 14 companies. On average, each pick yielded a 21% return, and my portfolio was up 25%. I also share a few key takeaways from this year in the market.

Headline Performance

The portfolio was started on March 5, 2025. Through December 31, the portfolio is up 25% vs. the S&P500’s 18%, while maintaining effectively zero correlation (0.0028) to the S&P.

On the General Market

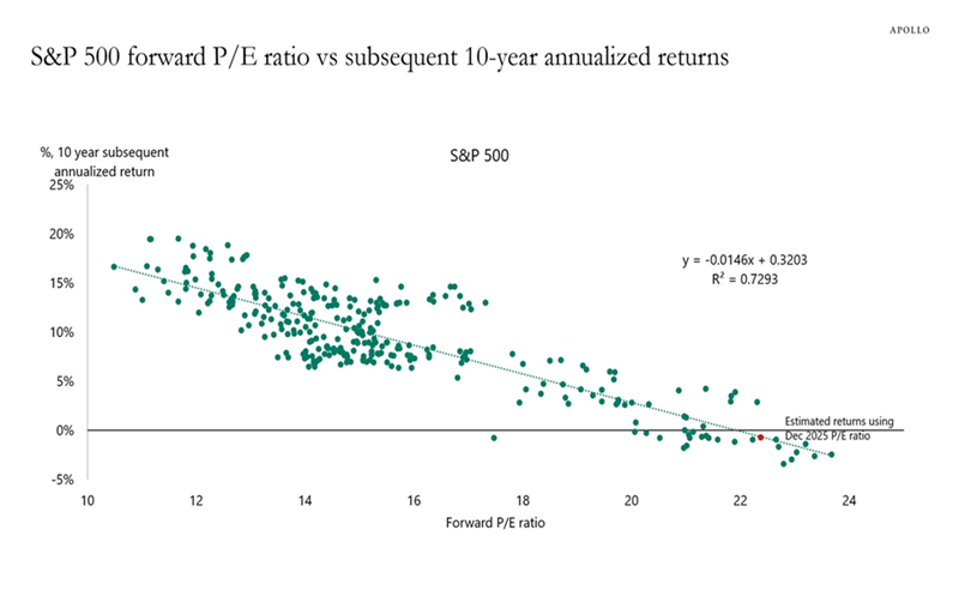

Based on historic long term returns in the S&P500, at these prices, you should expect an annualized return of -2 to 2% per year over the next 10 years. This makes it an unattractive investment.

Source: https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelfoster/2025/12/20/this-flawed-stock-chart-could-be-bad-news-for-investors-in-2026/

In investing, you are buying pieces of businesses. With the S&P500, I am not confident in those underlying businesses. 30% of the S&P500 is made up of companies that are betting heavily on AI, which means that if you are investing in the S&P500 you are betting that these AI investments will pay off. I am not so sure. Historically, overinvestment in innovative technologies (autos, radio, airplanes, internet) has not been a successful bet. I may be wrong, but I don’t know enough to make that bet.

Today, you are also buying some outrageous companies like Palantir and Tesla, which provide very little earnings for owners, have uncertain prospects for growth, and of which few people would want to be an owner if they were buying these companies alone (not packaged within the index). I don’t want exposure to these companies; I consider it risky, and mostly, I don’t like owning what I don’t know deeply. That’s why I prefer finding and buying mispriced companies that I understand on discount.

This year, I bought companies that I could understand at a price below their intrinsic value (at least 33% off). That is how I generated excess returns.

My portfolio heading into 2026 is positioned even better. It is now made up of companies that I own for at least 50% off their intrinsic value. I feel much more comfortable owning these than the general market.

Summary of Investments and Results

This year, I wrote up 14 businesses. I looked at over 300 to find these few worth writing about. In today’s market there is not much low hanging fruit. On average, each pick returned 22%, and since I held most of them for less than a year, the annualized return is higher. The benefit of owning companies whose value is unlocked by specific events is that once the event is passed, you can recycle your capital into other opportunities.

See here for full data of my results, links to my analysis, and a short note on each: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1O12UjLJzzisZ9umTSHacyJhZhYx4TsDGG-opjS6ZAKY/edit?usp=sharing

Best Performers

In absolute terms, EVC, LPRO, and TROX were my best performers. These fall in the bucket of general undervaluations. In case you missed them:

EVC, as covered on my Substack, was a broadcaster with significant “hidden assets” that were not being appreciated by the market. I valued each of its component parts: $200mn for the media assets, $100mn for its owned spectra, $200mn for its adtech platform Smadex, and $90mn in debt at face value. All together, $410mn in value was selling for $170mn (market cap). The market has since revalued the company for 73% more, closing the gap. However, I have also come to realize that my valuation for the hidden assets was likely overly optimistic (what is the value of something that does not generate cash flows and is unlikely to be sold?). Still, I bought it so cheap that I had a significant margin of safety to make an error in my valuation.

LPRO was a subprime auto lending platform that was a “disaster of the week” type situation. I covered it on SeekingAlpha. In Q1 it had to write down a significant chunk of its loan book, which was made in 2021-2022. The writedowns were so significant that the company stated a negative revenue for the quarter. Lawsuits were filed. The market was pessimistic. When I first looked at it in April, it was selling for $100mn, but had $110mn in net cash. It was like buying a house for $100mn and finding $110mn sitting inside—it was far too cheap. Further, when considering the context and extent of the writedowns, it was clear that future losses and writedowns of a similar magnitude were incredibly unlikely. It was shortly revalued by the market for 60% more.

TROX was a levered equity at the bottom of its cycle that I covered on VIC. Commentary on VIC seems to suggest that analysts were expecting it to breach its debt covenants by Q4 of 2025. What caught my attention was that management was buying shares on the open market. When I dug in more and read their debt agreements, it was clear to me that the terms of their debt were generous (very wide adjustments given for EBITDA), that they were currently in compliance with covenants (so could even raise more debt), and they had significant hidden levers to play to drum up cash, (at the time I focused on ability to make loans on working capital), all of which made a default outcome unlikely.

My thesis was soon confirmed by a $400mn debt offering by the company, and the stock repriced up 50%. I sold.

I still like this idea. TROX’s industry is at the bottom of its demand cycle, and when end market demand picks up, TROX will benefit significantly. They are vertically integrated into mines and moving into higher-quality ore deposits. They have recently been offered very attractive loan terms to better develop their rare earth mineral deposits, which provides them even more upside and potential liquidity. Here, you are waiting for end market demand to return to normal. If TROX makes it through to the upside of the cycle (likely when interest rates lower), you will do quite well here. However, India’s anti-dumping duties against TROX’s biggest competitor (LB Group) are no longer going into effect, and only one of another competitor’s (Venator) six plants appear to be fully closed. Additional competitor plant closures would have been more beneficial to the thesis.

I will also briefly highlight the NESR warrant exchange. When I published my Substack article on that, you could buy an NESR warrant for $0.50 and exchange it for 0.1 shares of NESR, which were $5.72 each (or $0.572 in exchange value). The underlying stock was also attractively cheap, selling at a PE of 5-6. By the time the exchange closed 3 weeks later, NESR was $6.33 a share. Total return was 27%, and IRR was 539%.

Biggest Mistakes & Lessons Learned

The most important thing I can do is reflect on my mistakes over the year, and four come to mind.

Magnera (MAGN)

David Bastian at Kingdom Capital had excellent coverage of MAGN this year. The situation is relatively simple. Magnera is a paper products company, formed from a combination of Berry’s paper division with Glatfelter Corporation. The paper industry was at a cyclical trough, and management was in the meantime successful in finding post-merger synergies. Assuming management’s expected future synergies were found and valuing the company on their expected mid-cycle cash generation (net operating profit of $350M a year), the stock was worth $18.97 / share. I bought at $12.59, but set a stop loss at $9. I never set stop losses, but in this case, the high level of debt made me concerned about the downside. If bad news about liquidity or debt hit, I would want out immediately, so I set a stop loss. Shortly after the stop loss was hit, MAGN had a good earnings season, and the stock appreciated to $15. The lesson here is to either avoid highly indebted companies entirely, or be so confident in your analysis that you don’t set a stop loss, and become comfortable in riding out downturns. Generally, I will lean towards the former.

Sunlink Health (SSY)

This was a merger arbitrage written up by Oliver Sung. It was a risk free 66-140% return in one month, easily the biggest no-brainer of the year. I only found out about it on Oliver’s follow-up post, which he made after the deal closed. I am a broke college student that can only afford one Substack subscription at a time, so subscribing to his Substack is not an option for me right now (but you should).

Instead, I built a web app to scrape SEC Edgar filings of all common special situation filings (DEF-14(s), SC14D9A, Form 10, SC-13E3, S1, and S4), and email me the key deal terms. In my special situations publication, I only post the situations that have not been arbitraged out yet, and so have found two or three interesting situations this year. The Sunlink Health deal terms were announced in a DEFM-14A filing, so I have paid particularly close attention to those. The only good deals thus far have been with companies that have very small market caps. I may have to better filter out filings to focus on those.

Moro Corporation (MRCR)

This was another no-brainer, and I don’t know why I missed it. Dirt covered it earlier this year at a 20% free cash flow to market cap yield, and priced at $2.60 a share. This week it was announced that the company was bought by a PE firm, Blackford Capital, Inc. for a 9% free cash flow to market cap yield, or for $5.59 per share.

Futurefuel (FF)

This one really made a lot of sense at the time. It was asset backed and selling below liquidation value, and seemed to be facing temporary problems with biodiesel production and regulatory uncertainty that should clear up. Regulations were clarified, and biodiesel production was restarted, but cash flows did not materialize as I expected. This industry is highly complex with many moving parts and many things that can go wrong. It is a government created industry, many government policies at many different levels have to work in concert for the end markets to be profitable for biodiesel producers. This administration has made some choices that are friendly to biodiesel and some that are not, and the regulations made by different federal departments have been contradictory. The economics of feedstocks and oil prices have moved in an unfriendly way this year. The market for RINs appears oversupplied. The company doesn’t seem like it will be able to transition production to a new product, so we are stuck with the challenge of handicapping the complexities of biodiesel policy and economics going forward.

In investing, we often refer to the engineering concept of “margin of safety”: If you want to build a bridge to withstand 100 expected tons of traffic, you should build in an additional margin of safety to withstand, say, 150 tons. I think a similar engineering concept applies here, and that is “complexity reduction.” A simple system has fewer things that can go wrong, and fewer things to control for. Over the long run, a simple system will be more reliable than a more complex one. I think it is much the same in investing. Going forward, I will avoid industries as complex as biofuels. My winners have been very simple ideas, and I should find success in sticking to simplicity.

Conclusion

I feel good about the year. I outperformed the S&P500 with zero correlation. I recently wrote an article about why beating the S&P500 is so difficult, and why so few fund managers are able to do it, and I would recommend you read it for context on this.

More importantly, I learned a lot this year, and knowledge compounds. Each company you look at adds to a web of knowledge that you can pull on as you continue to read and learn about each additional company.

Four specific takeaways stand out to me:

The first is that complexity should be reduced as much as possible. If the situation is too complex and relies on too many moving parts, your confidence in arriving at the right conclusion should be reduced. I had enough great simple ideas this year that cutting out the most complex ones wouldn’t have had much of an impact.

The second is that excessive leverage should be avoided, and once leverage is avoided, stop losses are not necessary.

The third is to focus on illiquid stocks. In public markets, your returns are based on your competition. If you go up against the best hedge funds in the world with the smartest talent, better information, and better technology, you are much less likely to succeed against that competition. However, there are parts of the market where you can compete against no hedge fund. That happens in tightly held and thinly traded securities.

For example, say a small hedge fund manages $300M in capital. An average position is 5% of the portfolio or $15M. Now say there is a company that trades $100,000 worth of shares per day. In order to build a position without moving the market, you would need to buy less than 20% of the shares a day, and it would take you 750 trading days or 3 calendar years to enter the position. As you can imagine, no fund would do this—and none do.

Some of the most interesting ideas of the year fell into this category: NESRW, Sunlink health, and Moro.

There are a few more considerations about investing in illiquid names that I think are important and that I will write about shortly.

Overall, portfolio management and position sizing was a weak spot this year, but the quality of the average position was enough to overcome that. Going into 2026, I feel much more confident in my “value investing” philosophy: That you can generate satisfactory returns if you buy what you know for less than the value of its future cash flows.

Also, a post detailing my current positions will be released soon, stay tuned.

Thanks for the mention!

Thank you for sharing all this. I’ll be pledging my support as I think your macro analysis fits my general themes, but with more detail.

I had my best year ever, *37.2% and that is with a 60% allocation to cash. 23% gold and silver. 17% equities, mostly mining and energy which are the only two industries I understand. Plus a foreign bond fund that delivered 12%. Onward to 2026.